UFC Judging Analysis:

The goal of this project was to identify the importance of relevant factors in UFC Judging and identify how individual judges value these factors differently. This began as my Senior Thesis project that was completed in May 2024 at Syracuse University, and I have since improved upon the methods as well as added to it.

Project Highlights:

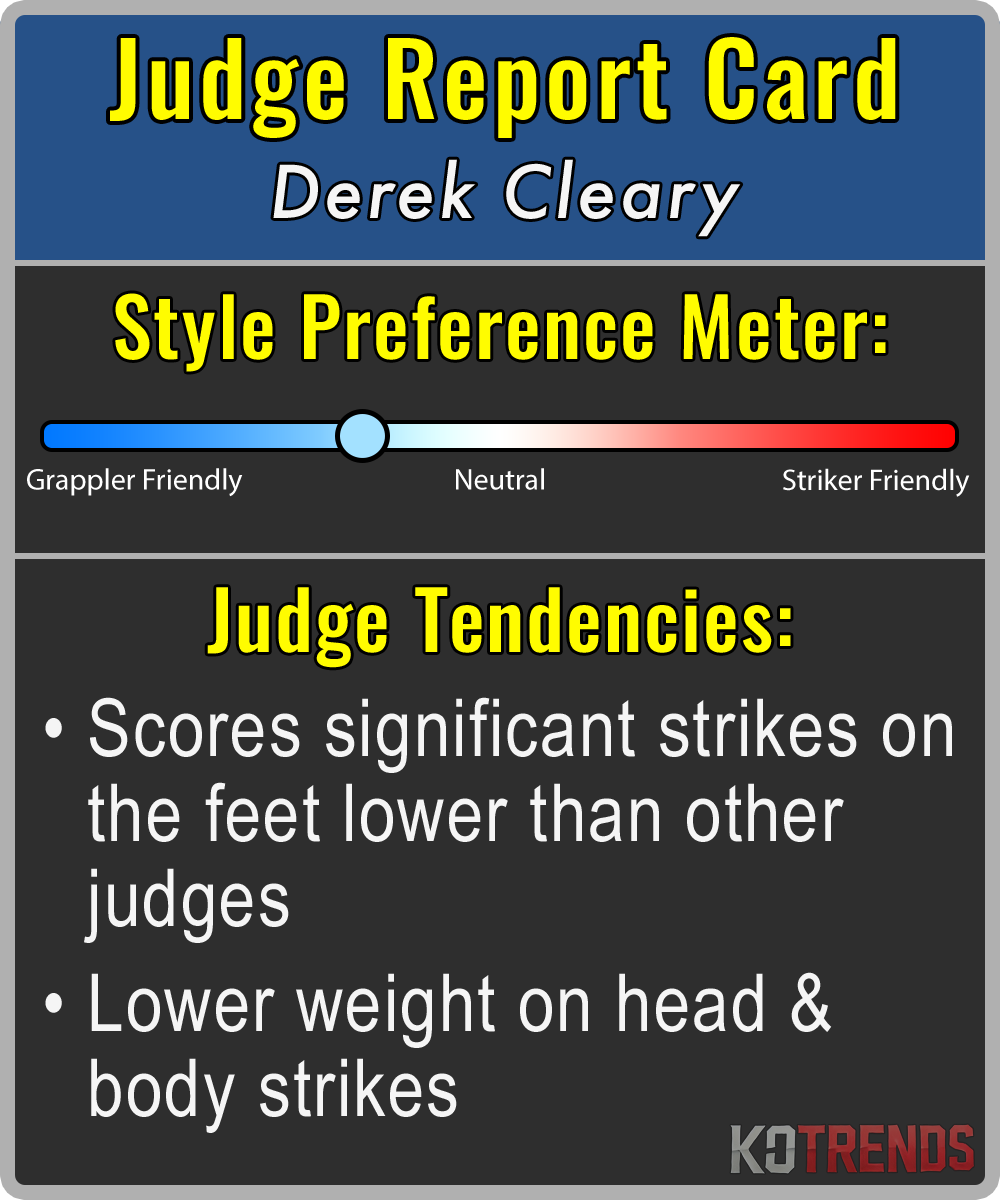

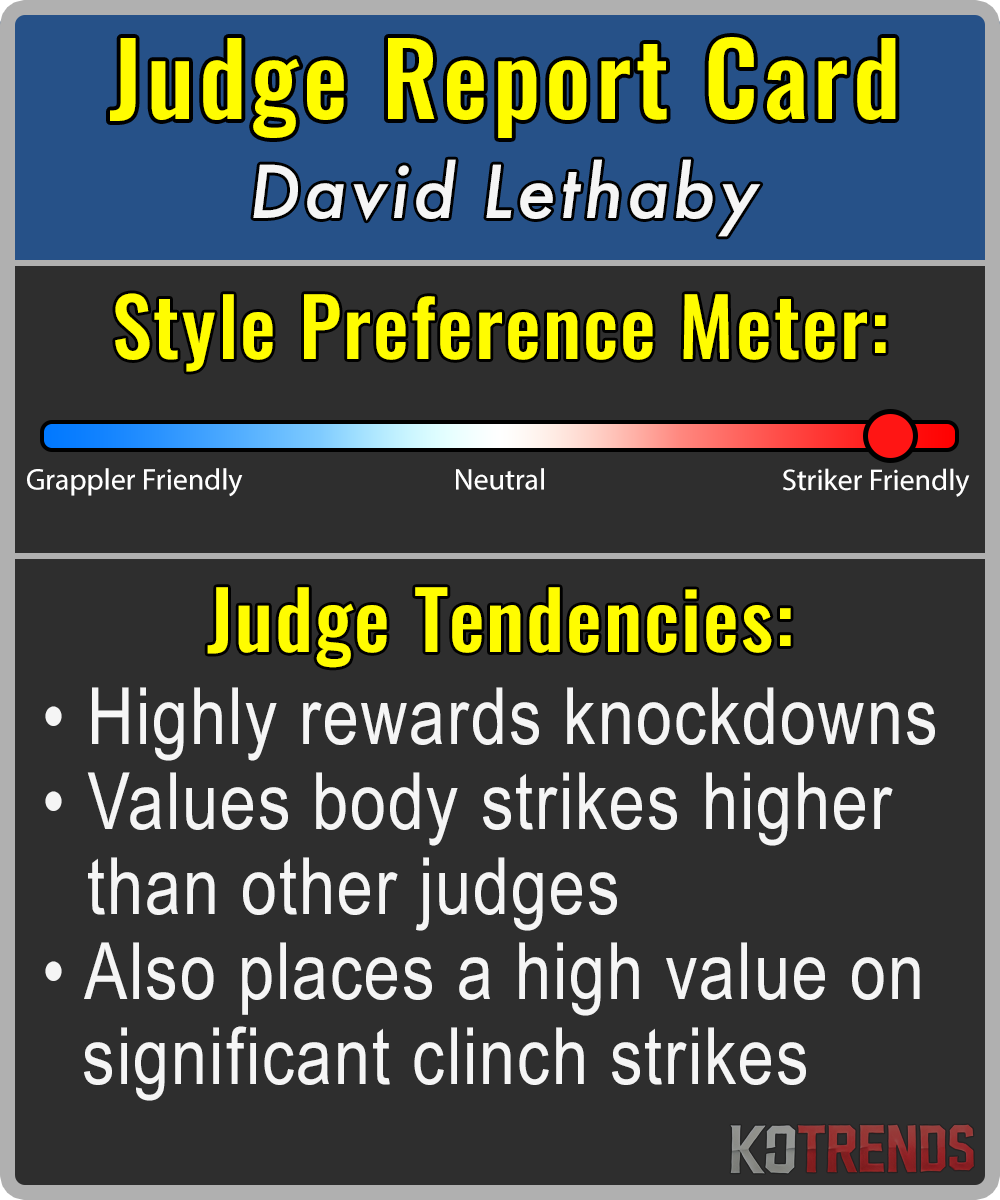

Utilizing binomial glm models that predict round winners for each judge, I was able to identify individual judge tendencies and created a metric that measures their preference of strikers versus grapplers. These findings are visualized in concise judge report cards:

Project Walkthrough:

Data & Methodology:

Round by round scorecard data was scraped from mmadecisions.com. The fight data used for this project was scraped from ufcstats.com.

The fight data included significant strikes landed with two different breakdowns. The first breakdown, which I will refer to as the target data, is broken down by whether the strike was landed to the head, body or legs. The second significant strike breakdown is by whether they were landed at distance, in the clinch or on the ground, so I will call this the positional breakdown. Aside from significant strikes landed, the fight data also included knockdowns, non-significant strikes landed, control time, takedowns landed, reversals and submission attempts.

In order to remove the red vs. blue corner effect, I randomly assigned each fighter’s data to one of two sets of columns. After fighters were randomly assigned for each round, I calculated the difference between each of the statistics mentioned above between the two fighters. The differences of these statistics will then be used to predict the win probability of fighter 1 in the models.

Binomial GLM Models:

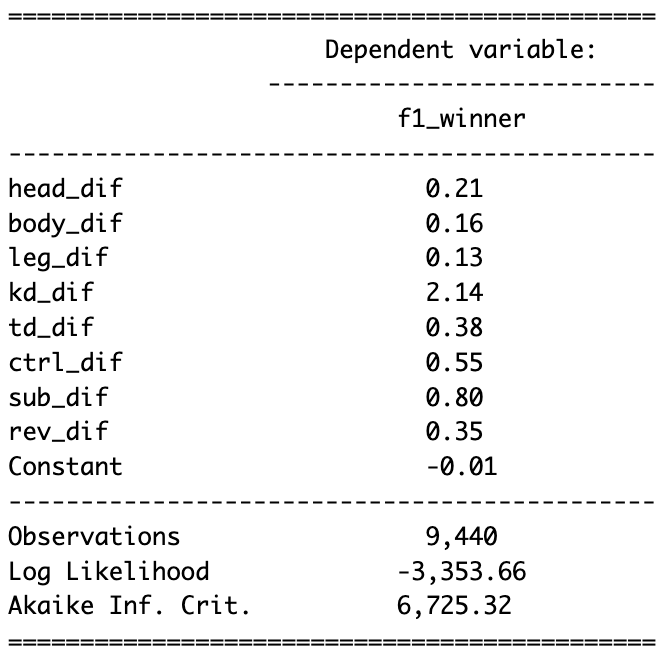

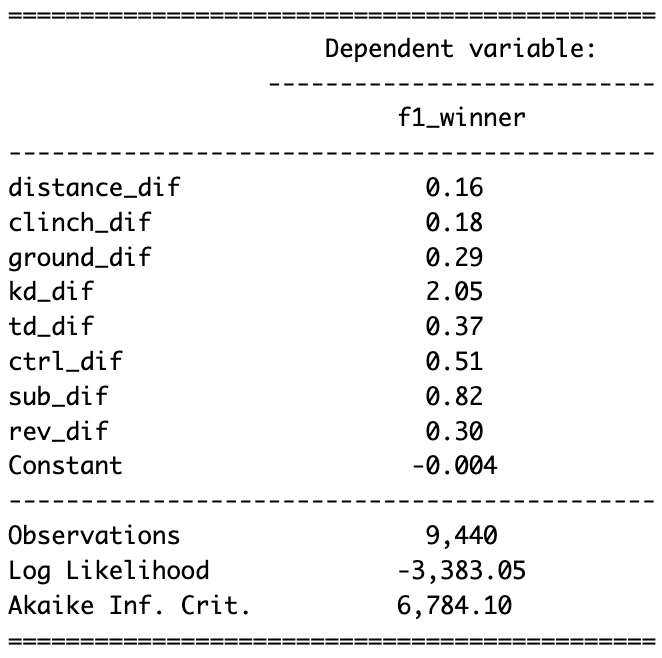

Here are the results of the binomial GLM models ran using each of the avaiable significant strike breakdowns:

You can see that the target model has identified the head as the most important target to the judges. Both models also backs up the fact that knockdowns are extremely impactful to winning rounds. Takedowns and reversals are valued essentially the same, and will improve the log odds of winning a round by about as much as 50 seconds of control time. A submission attempt is valued more than twice as highly as a reversal or takedown.

You can see that the target model has identified the head as the most important target to the judges. Both models also backs up the fact that knockdowns are extremely impactful to winning rounds. Takedowns and reversals are valued essentially the same, and will improve the log odds of winning a round by about as much as 50 seconds of control time. A submission attempt is valued more than twice as highly as a reversal or takedown.

Because all distance strikes are defined as significant strikes, it makes sense they have the lowest significant strike coeficcient in the position model. The scorer had to manually deem significant strikes in the clinch & on the ground strikes as significant based on power, but even the lightest distance strikes are considered significant.

Individual Judge Biases:

After the glm models were created, I was able to use these to indetify individual judges’ scoring biases. In order to do this, a subset of the data was created for each judge to be examined. I then repeated this process for each of the judges:

- Two new winner variables were created. Judge winner indicated who the selected judge had winning the round, and Non-judge winner was the winner selected by the other two judges. Rounds where the other two judges disagreed were dropped.

- These new variables were used to create two models for each judge: The Judge model fitted on the Judge winner variable and the Non-judge model fitted on the Non-judge winner variable.

- A wald test was run to test if the differences of the coeficcients between the two models were significant, and a graph was created to compare the coeficcients.

This Process was also repeated using both the target & position model to examine all variables

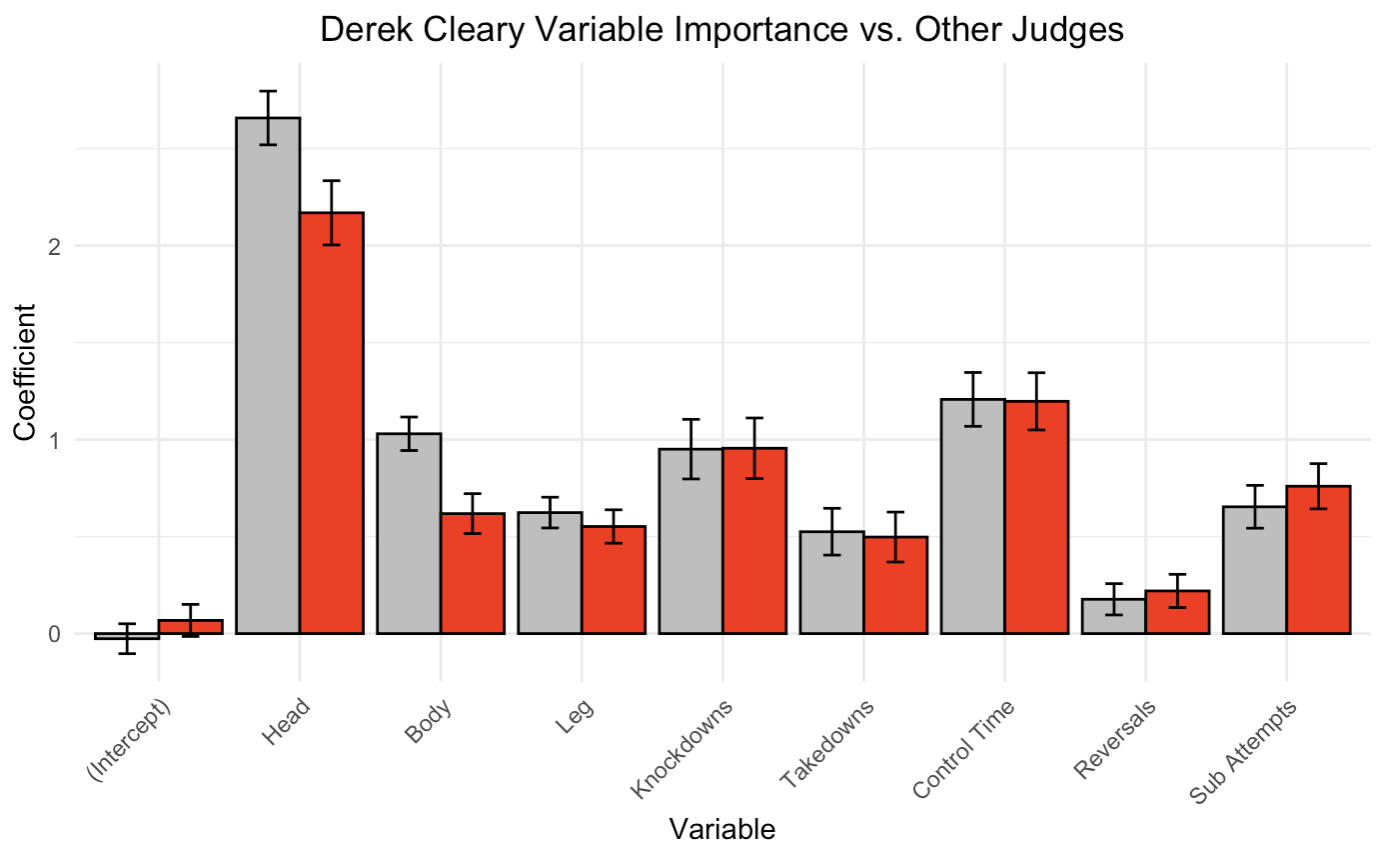

Here is an example of the target output graphs for one of the judges (Derek Cleary):

Looking at the error bars, you can see that there is a statistically significant difference in how Derek Cleary (red) values significant strikes to the head & body compared to other judges (Cleary scores them both lower). While not statistically significant, we can also see that he seems to have scored submission attempts slightly higher.

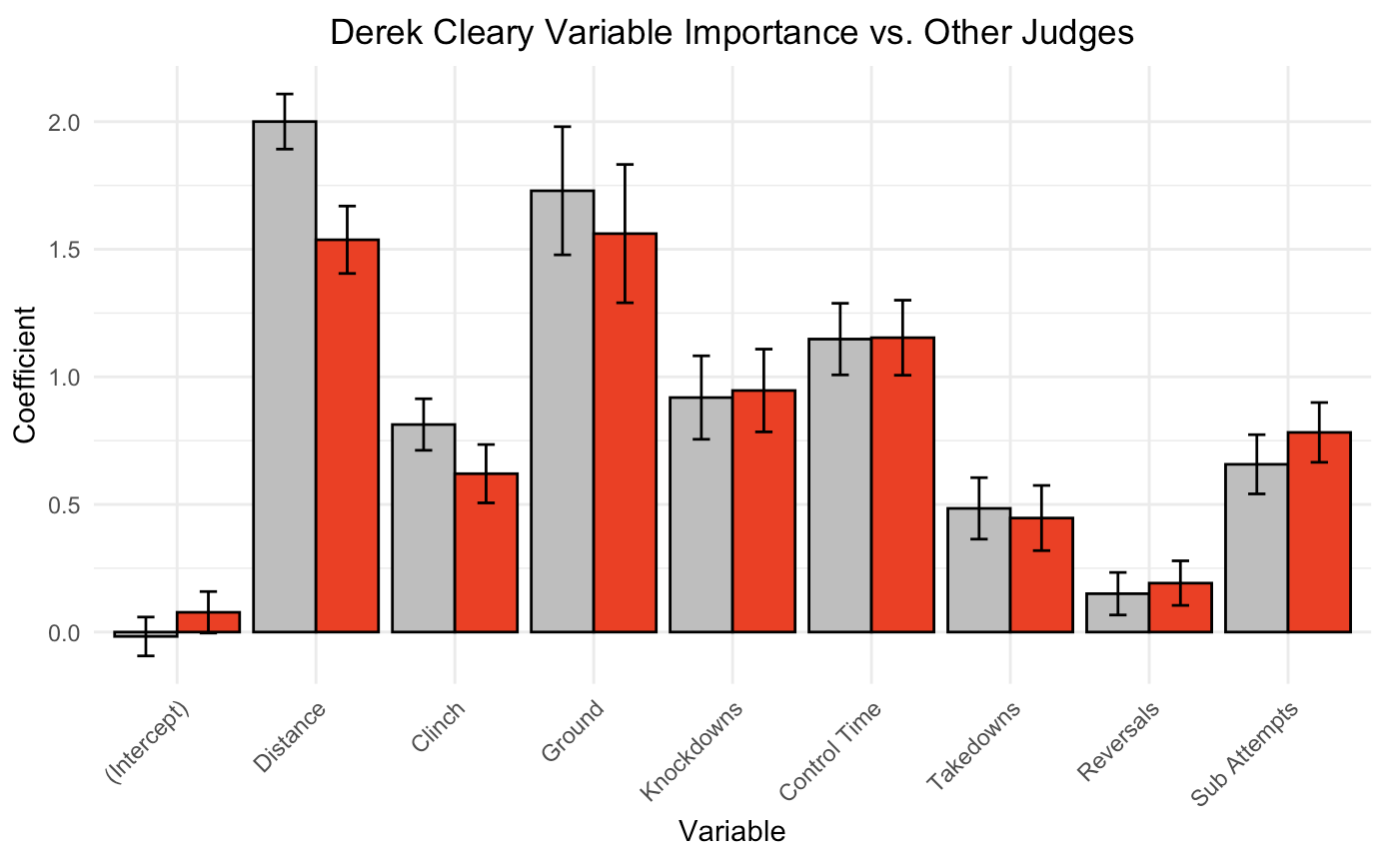

We can also examine the alternative graph for the position models:

In this graph, the only statistically significant difference that can be seen is in significant distance strikes.

Striker-Grappler Preference Scores:

While the graphs above do a good job of showcasing specific judge tendencies, I also wanted to create a single metric that identifies their preference of strikers versus grapplers. In order to do this, the position model was used and the predictors were first broken into striking and grappling predictors.

Striking predictors:

- Significant distance strikes

- Significant clinch strikes

- Knockdowns

Grappling predictors:

- Significant ground strikes

- Takedowns

- Control time

- Submission attempts

- Reversals

Using the same Judge & Non-judge models from earlier, I then repeated this process for each judge:

- 4 values were calculated: strj (sum of the judge model striking coeficcients), graj (sum of the judge model grappling coeficcients), strnj (sum of the non-judge model striking coeficcients) and granj (sum of the non-judge model grappling coeficcients)

- ratiostr was calculated as strj/strnj and ratiogra was calculated as graj/granj

- The final sgps score was calculated as log(ratiostr/ratiogra)

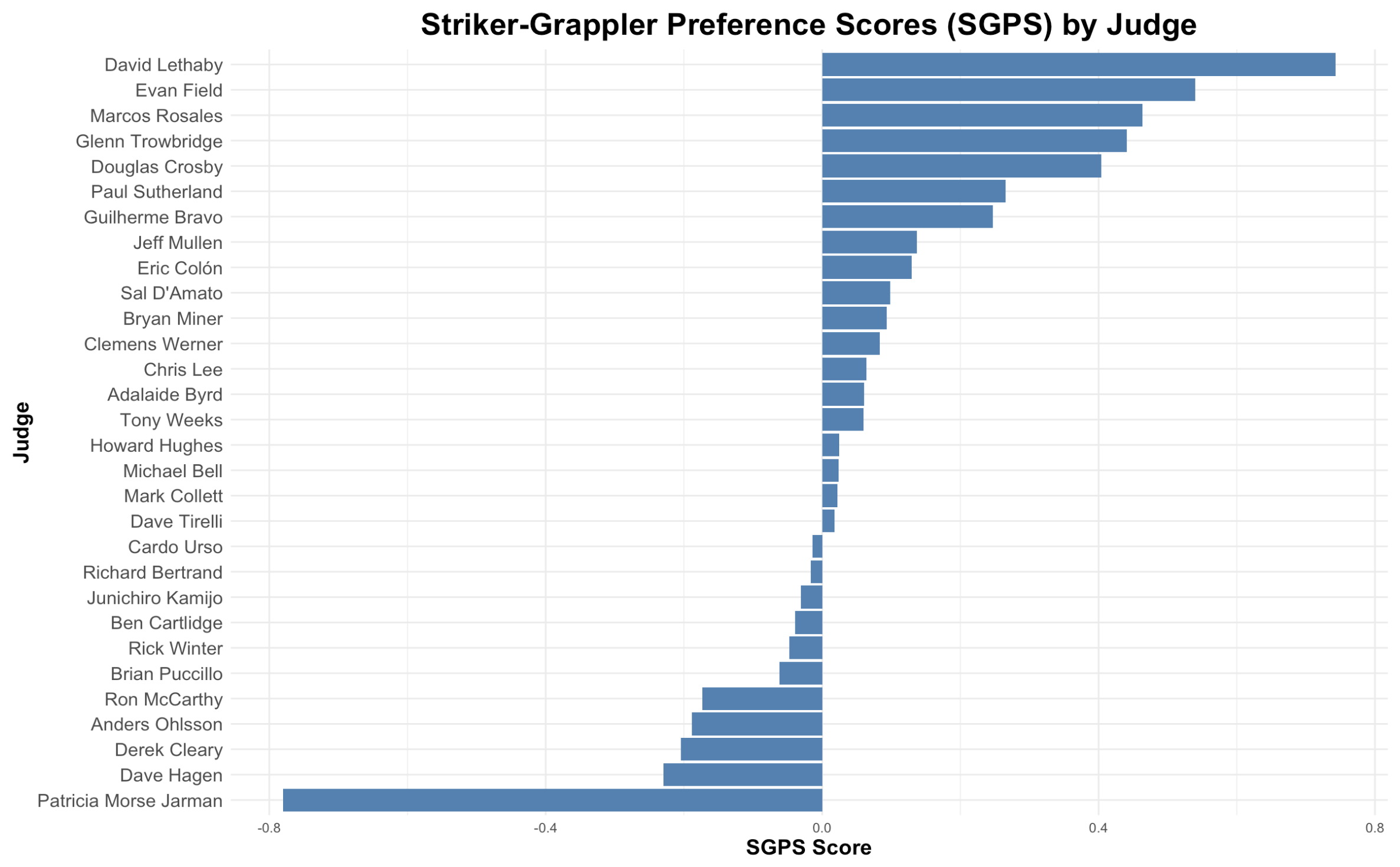

With this formula, positive sgps numbers represent a striker preference whereas negative numbers indicate a grappler preference. The following graph showcases the striker vs. grappler preference of the 30 UFC Judges with the most rounds judged:

Judge Report Cards:

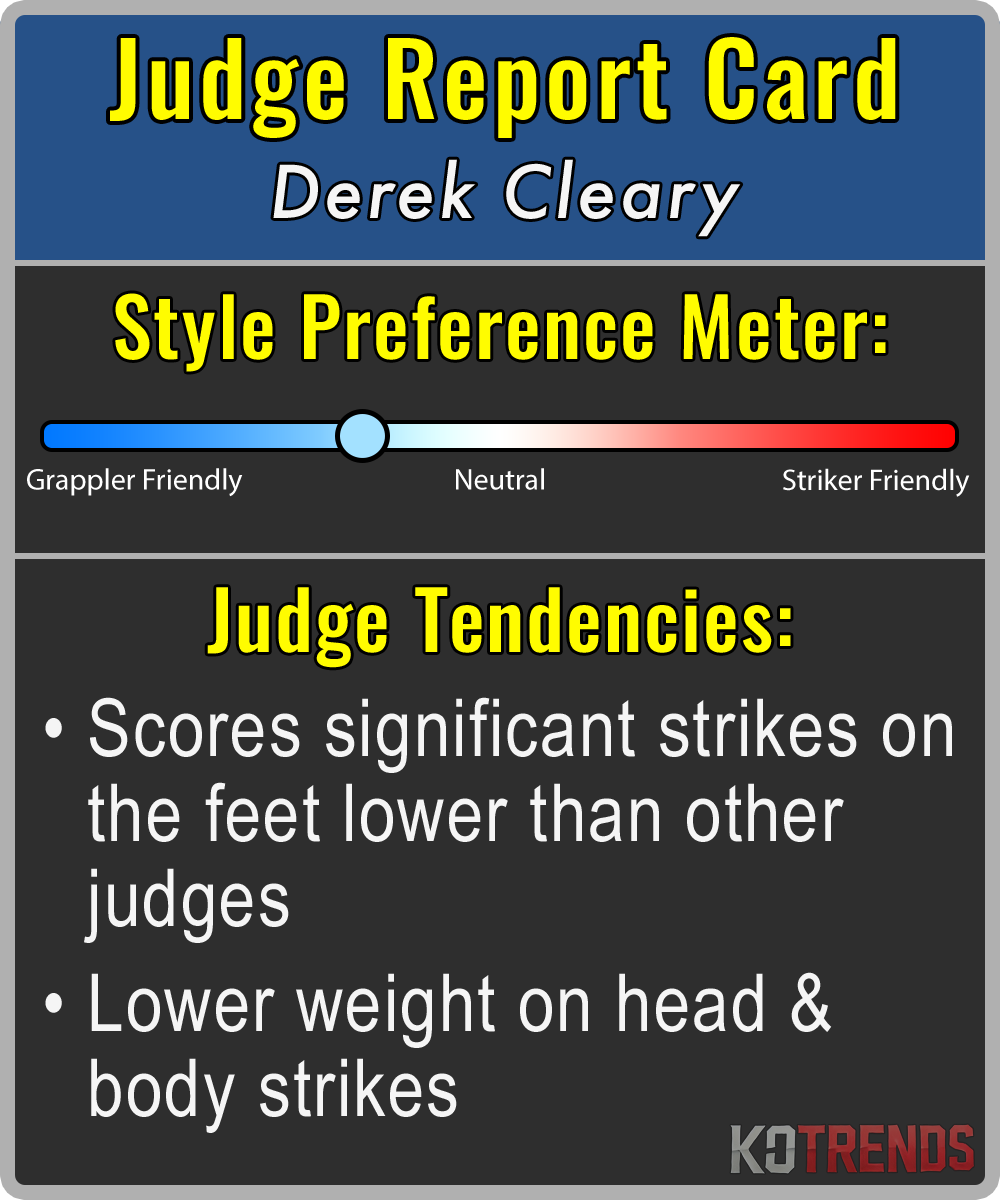

Utilizing the sgps scores created along with the coeficcient difference graophs above, I have creaated judge report cards for many of the judges with a high amount of rounds judges. Here is an example of the report card for Derek Cleary, whose coeficcients we examined earlier:

Decision Tree & Random Forest Models:

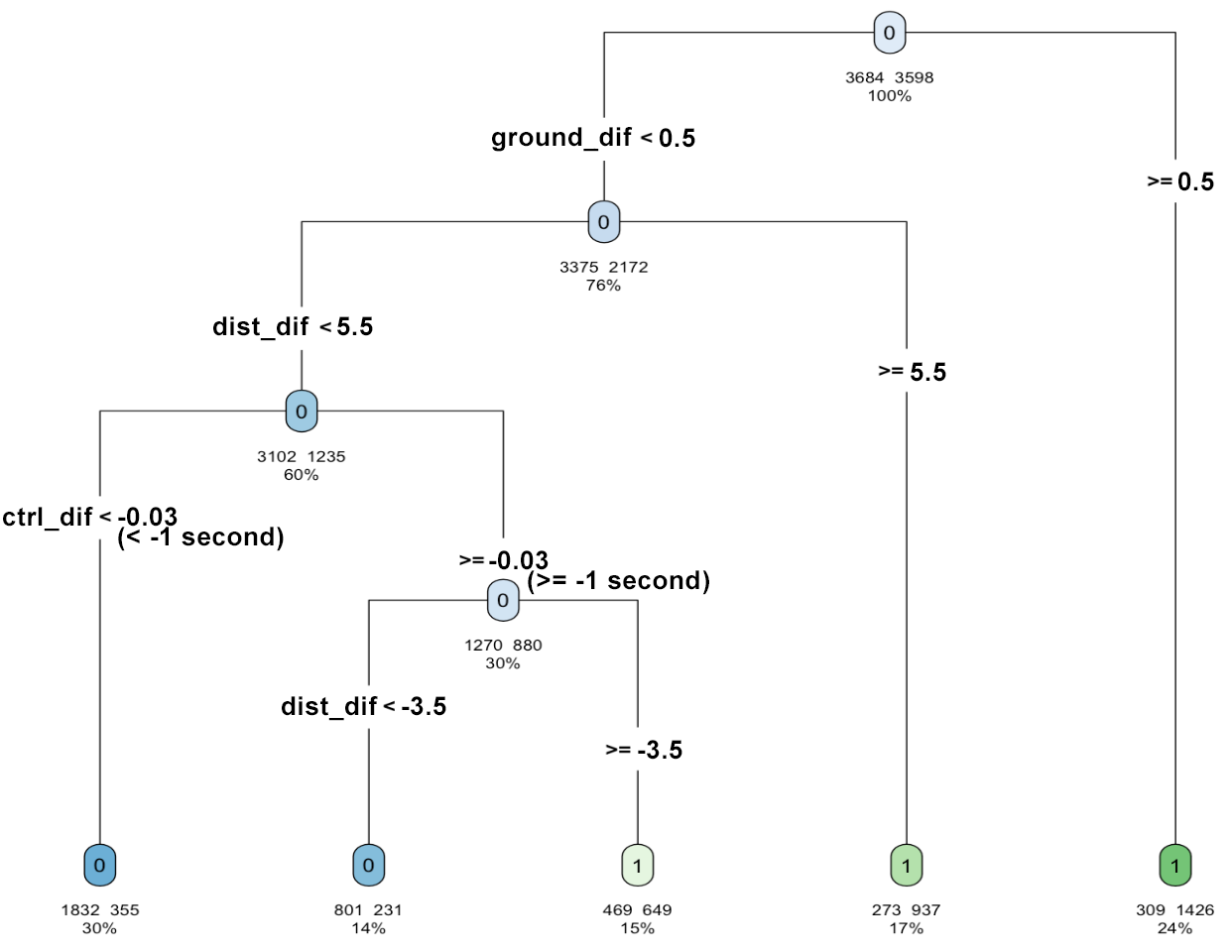

In addition to the binomial GLM model created, a decision tree and random forest were created to judge rounds. Most of the variables are the same here, but instead of the significant strikes being broken down by target (head, body legs), they are broken down by where the striking occured (distance, ground or clinch). This data will allow the decision trees to identify different types of fights, such as a round where one fighter dominated on the ground but lost on the feet. The main decision tree is shown below:

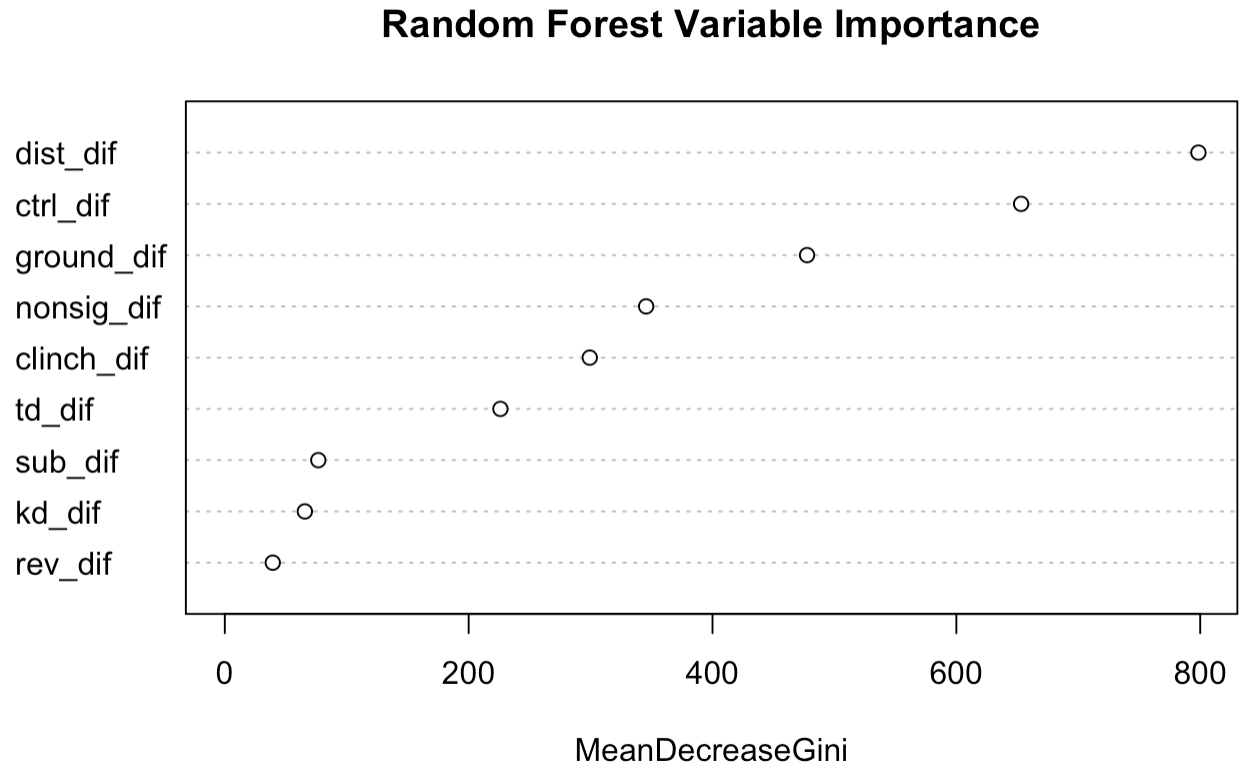

You can see that this tree has multiple splits based on who won the distance striking as well as the grappling (through ground striking and control time). While this overfits the data, you can see how this approach makes sense for scoring. A random forest model using the same predictors was also created, and the following output shows the results of this:

You can see that this tree has multiple splits based on who won the distance striking as well as the grappling (through ground striking and control time). While this overfits the data, you can see how this approach makes sense for scoring. A random forest model using the same predictors was also created, and the following output shows the results of this:

Just like in the decision tree significant distance strikes, control time, and significant ground strikes are the most important predictors. Significant clinch strikes do not have much of an impact, and the mean decrease gini is actually higher for non-significant strikes. Takedowns are not overly important due to most grappling splits occuring on control time and ground striking. Submission attempts, knockdowns, and reversals all occur infrequently so the random forest was unable to capture the importance of these.

Just like in the decision tree significant distance strikes, control time, and significant ground strikes are the most important predictors. Significant clinch strikes do not have much of an impact, and the mean decrease gini is actually higher for non-significant strikes. Takedowns are not overly important due to most grappling splits occuring on control time and ground striking. Submission attempts, knockdowns, and reversals all occur infrequently so the random forest was unable to capture the importance of these.

Read my thesis: Analysis of UFC Judging Criteria (Spring 2024)